Introduction to the new approach to obesity: Results of an expert commission

On January 14, 2025, the results of a commission composed of medical specialists and researchers were published in The Lancet Diabetology & Endocrinology. Their goal was to rethink the framework for understanding and managing obesity¹. Globally, the World Health Organization reported that in 2022, 1 in 8 people had obesity, including 890 million adults and 160 million children and adolescents. Since 1990, the number of adults with obesity has doubled, while the number of children and adolescents has quadrupled, making obesity a major public health concern worldwide. Obesity is associated with numerous clinical complications of varying severity, significantly affecting health and quality of life, as well as placing a substantial burden on national healthcare systems².

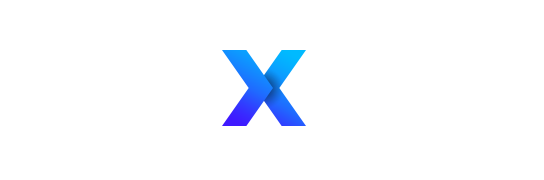

A New Definition of Obesity: Beyond BMI

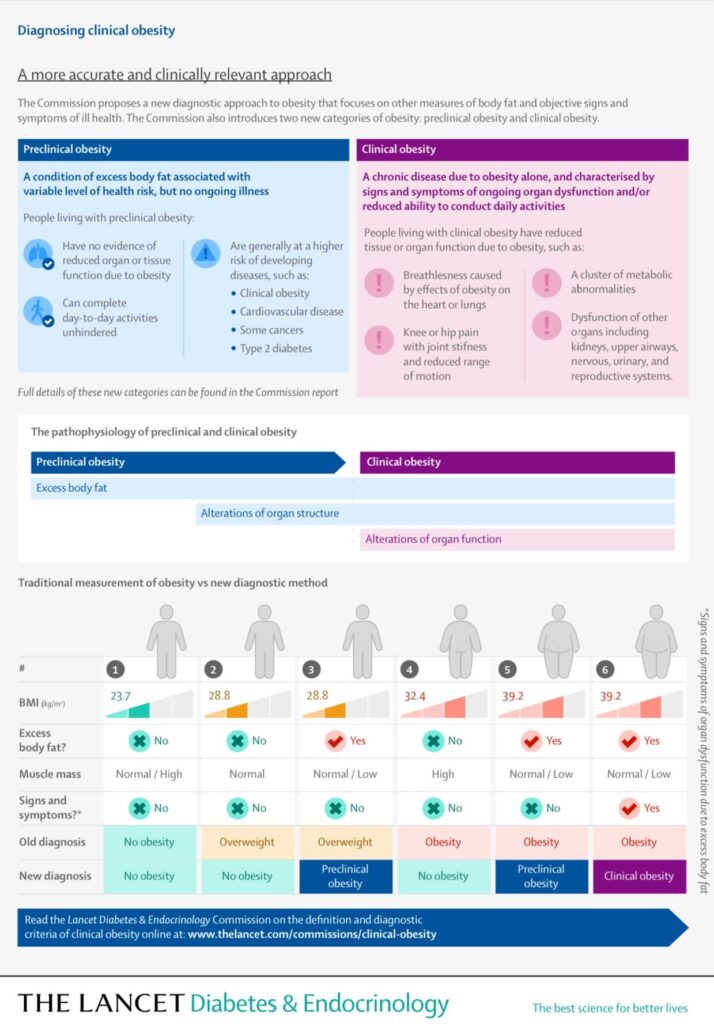

The main outcome of this commission was the proposal of a new definition that redefines the way obesity is understood and managed. Until now, obesity was solely defined by a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m². However, this definition did not consider individuals’ body composition. As a result, healthy individuals with a BMI above 30 kg/m² but with high muscle mass and a normal or slightly elevated fat mass were mistakenly classified as having obesity. This often led to misdiagnoses and/or inappropriate recommendations. To prevent this, the commission has proposed that obesity should be defined as a BMI greater than 30 kg/m² combined with excess fat mass.

The Importance of Body Composition in Diagnosing Obesity

Practically, this means that it is now necessary to assess fat mass, either directly or indirectly, to diagnose obesity and monitor its progression. For direct measurement, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and/or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) are recommended. Indirect measurement involves anthropometric assessments, such as waist circumference, when direct measurement is not possible. Additionally, it is recommended to use a direct fat mass measurement during obesity management to:

- assess the effects of treatment on body composition.

- tailor treatment according to each patient’s needs and capabilities;

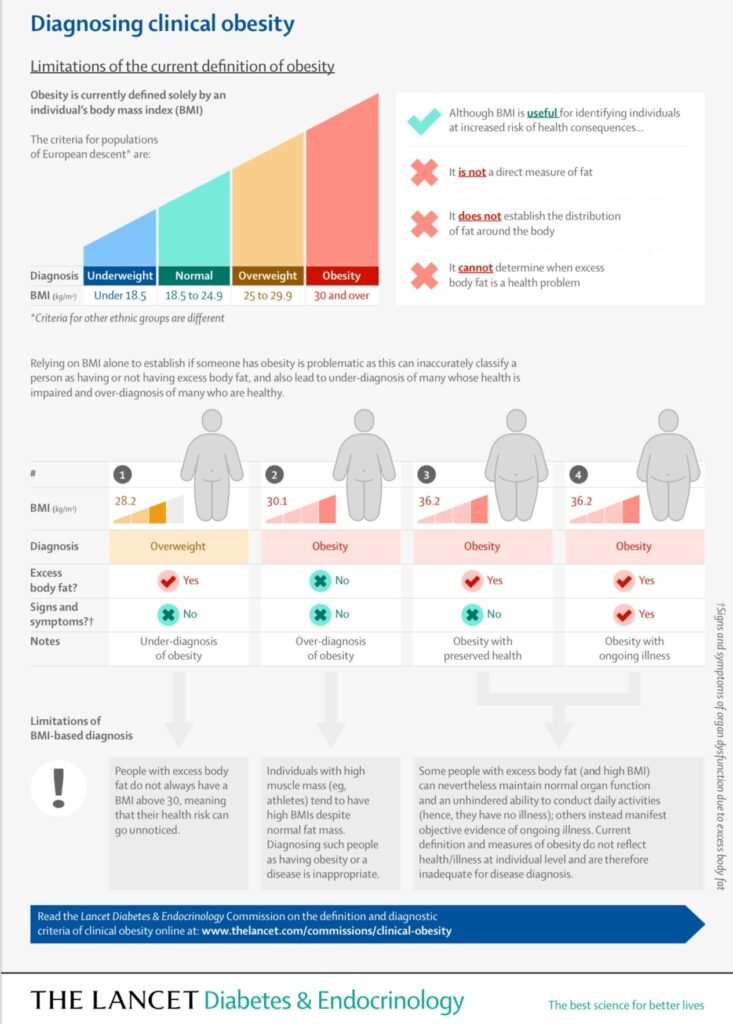

Two Categories of Obesity: Preclinical and Clinical

In addition to this new diagnostic definition, the commission also proposes categorizing individuals with obesity into two groups: preclinical obesity and clinical obesity.

Preclinical Obesity: This is defined as a BMI greater than 30 kg/m² with excess fat mass but without clinical complications or organ dysfunctions, or with dysfunctions caused by excess fat mass. For example, hypothyroidism prevents the body from utilizing lipids from adipose tissue, leading to an accumulation of fat mass. In this case, hypothyroidism is the cause of obesity, classifying it as preclinical obesity. Preclinical obesity can also be present in individuals with obesity who do not exhibit dysfunctions or have silent, non-pathological alterations. These individuals may either be healthy or have predispositions to clinical obesity that could be managed through lifestyle modifications.

Clinical Obesity: This is defined as a BMI greater than 30 kg/m² with excess fat mass, along with one or more organ dysfunctions directly caused by lipid accumulation. The most common dysfunctions include:

- Metabolic disorders, leading to conditions such as type 2 diabetes or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (commonly known as fatty liver).

- Cardiovascular complications, such as heart failure, high blood pressure, or an increased risk of stroke.

- Musculoskeletal disorders, such as osteoarthritis or muscle dysfunction, which can result in sarcopenic obesity.

Clinical Complications Associated with Clinical Obesity

These obesity-related disorders are well-documented in the literature²-⁴. However, they have traditionally been treated separately from excess fat mass, often leading to pharmacological interventions that do not address the root cause. This separation has resulted in treatments that manage symptoms without integrating the underlying causes into the therapeutic strategy. The new definition allows for a paradigm shift in obesity management by treating the individual holistically and developing therapies that specifically target these clinical complications while promoting sustainable lifestyle modifications⁵.

The goal is to: reduce fat mass and its harmful effects on health; establish long-term habits that maintain overall health, particularly fat loss and muscle mass preservation or gain.

The two most effective strategies to achieve this are physical activity and nutrition, as they are powerful interventions for modulating these body composition components⁶-⁸.

The Importance of Considering Body Composition in Treating Obesity-Related Complications

In clinical practice, the use of approaches specifically targeting body composition creates a need for assessment techniques that:

- guide precise obesity management;

- monitor and adjust treatment over time, similar to how blood pressure is managed.

For this purpose, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is a highly relevant technique, as it provides a quick and non-invasive way to assess individuals’ body composition⁹-¹⁰.

Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis: An Essential Tool for Long-Term Obesity Management

Looking ahead, BIA is expected to become an increasingly essential tool for monitoring obesity patients throughout their treatment, with the goal of improving their health and quality of life.

References

- Rubino F, Cummings DE, Eckel RH, Cohen RV, Wilding JPH, Brown WA, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. janv 2025;S2213858724003164.

- Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 19 janv 2017;376(3):254‑66.

- Forouhi NG. Embracing complexity: making sense of diet, nutrition, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 14 févr 2023;66(5):786.

- Patterson E, Ryan PM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, et al. Gut microbiota, obesity and diabetes. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1 mai 2016;92(1087):286‑300.

- Kushner RF, Sorensen KW. Lifestyle medicine: the future of chronic disease management. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. oct 2013;20(5):389‑95.

- Damas F, Phillips S, Vechin FC, Ugrinowitsch C. A review of resistance training-induced changes in skeletal muscle protein synthesis and their contribution to hypertrophy. Sports Med. juin 2015;45(6):801‑7.

- Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. déc 2015;25 Suppl 3:1‑72.

- Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P, Ballmer P, Biolo G, Bischoff SC, et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr. févr 2017;36(1):49‑64.

- Mulasi U, Kuchnia AJ, Cole AJ, Earthman CP. Bioimpedance at the bedside: current applications, limitations, and opportunities. Nutr Clin Pract. avr 2015;30(2):180‑93. 10. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gómez J, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin Nutr. déc 2004;23(6):1430‑53.